Windows of Astronomy |

||

PhotographyFollowing experiments by Nicéphore Niépce and Fox Talbot in the 1820s, photography became a commercial proposition in the hands of Daguerre in the 1830s. Even by mid-century, photographic plates were extremely insensitive (‘slow’). The only astronomical photography possible in the 1850s was imaging the Sun and Moon. In spite of their brightness, these objects demanded exposures of minutes. In the early 1870s the chemistry of photography changed from the ‘wet collodion’ process, where plates were prepared in liquid just before the exposure, to ‘dry plates’ that could be prepared well in advance so long as they were kept in total darkness. Dry plates were being made that were increasingly fast, allowing star fields to be imaged. Exposures could still be 20 minutes or sometimes longer. Keeping a telescope pointing directly at the stars as they moved around the Earth so that the image on a photographic plate did not move by the width of a dot was at first beyond the accuracy of telescope tracking clockwork of the time. New telescope drives were developed but even with them the observer generally had to look through supplementary optics and keep a chosen star exactly on cross-wires. This led to the development of the ‘astrographic telescope’. It was essentially two telescopes strapped together, one for a large photographic plate and one with an eyepiece for the observer. Taking good photographs in the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century still required a sharp eye and a lot of patience. David Gill, an Aberdonian who was Her Majesty’s Astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope, made the first photographic star catalogue in the 1880s to 1890s with the assistance of Jacobus Kapteyn of Leiden University. This contained over 450,000 stars down to 9th magnitude, about a twentieth of the brightness of the least visible naked eye stars. The catalogue took some 10 years to prepare, which was only about a quarter of the time a comparable northern hemisphere catalogue had taken using ‘eyepiece astronomy’. Photography was clearly the tool of the future and Gill in collaboration with over 20 other observatories embarked on a whole-sky catalogue including stars a hundred times fainter than the earlier survey. Photography would be the key to finding what was out there beyond the range of the eyepiece. |

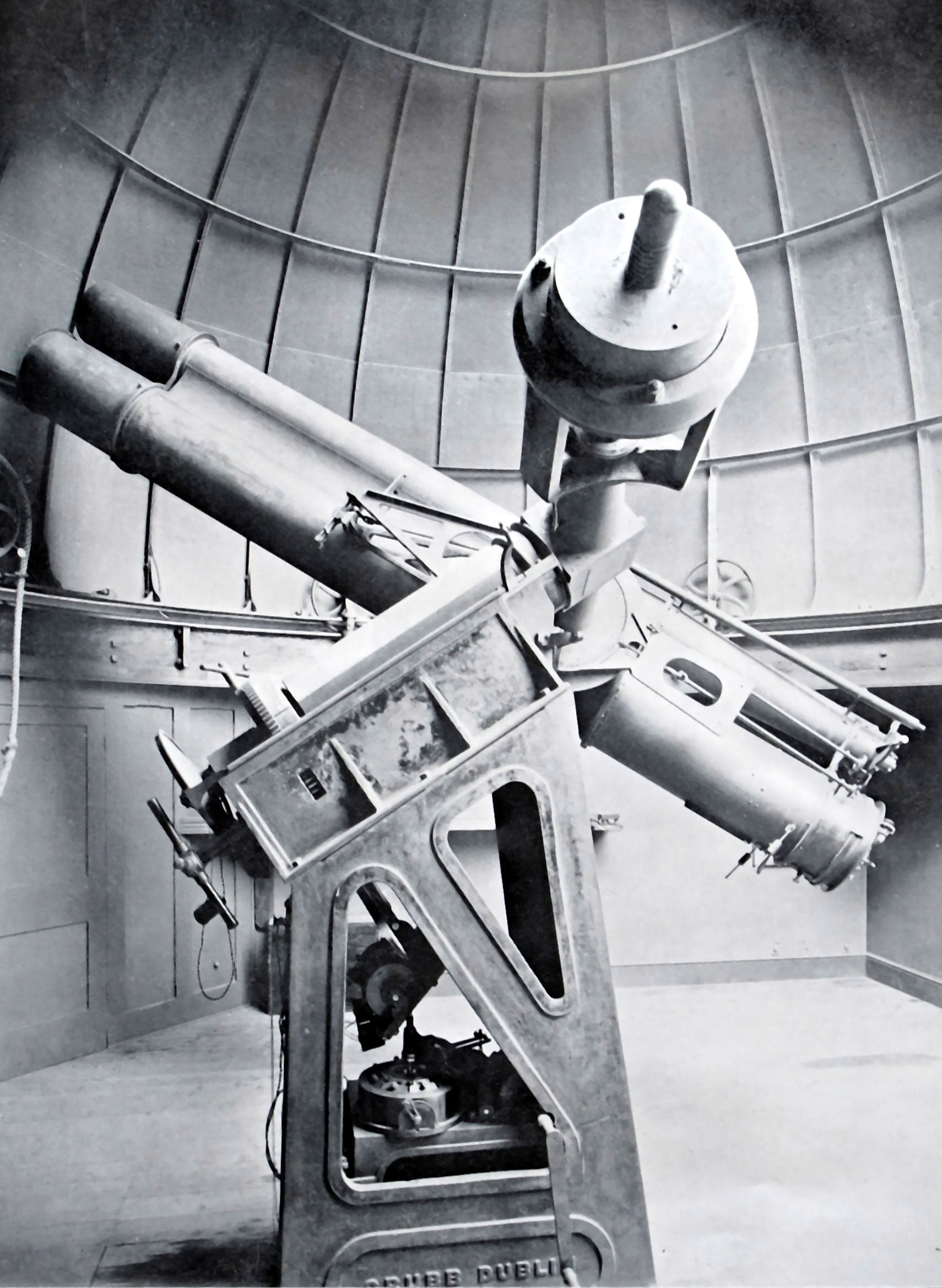

David Gill’s astrographic telescope in South Africa |

|

Photography made it very clear that some nebulous objects in the sky were gaseous and some were star clusters. With photography, other galaxies were discovered and the Milky Way seen to be simply our neighbourhood in the suburbia of the ‘local cluster’. Galaxies in the Universe have turned out to be as common as stars in the Milky Way and the oft-quoted figure is that there are more of them than grains of sand on the Earth. Galaxies are not all the same size nor all the same shape. How the population of galaxies that we observe today has come about is an unfolding story in astronomy. Glass backed photographic plates were used until well into the second half of the twentieth century. They were more stable than film. Towards the end of the twentieth century photography changed rapidly from chemistry to physics. With the advent of CCD detectors (charge coupled devices), fields of view were divided into pixels and images directly recorded digitally. The new technology preserved the fundamental strength of photography, namely that the camera accumulates the effects of generally faint light over the whole exposure time. Eyeballs just respond to the illumination of the moment. With the new digital technology has come digital image processing that further increases the information recorded in each image. Photography still provides the foundation of astronomy, with many other techniques adding a wide range of detail to our knowledge of the universe at large.

|

Photography revealing Messier’s faintly seen blur M83 as a spiral galaxy 15 million light years away. Courtesy ESO. |

|